“Stick in”, a phrase I associate with James Slater, Pa as we called him, my maternal grandfather. Born in poverty, he crossed the globe, returned to Orkney, bought and grew his own farm, working hard and innovatively. (It should also be said that I write from the perspective of the first child of his favourite child.)

Early life

Pa, eighth child of William Halcro Slater and Tomima Groundwater, was born at Gara, Orphir on 24 March 1890. (“Gerra” on this map.) From the very start, life was challenging as the family was forced to apply for poor relief a few weeks before the birth, the reason being his father’s “insanity”. In William’s case, “insanity” probably meant depression severe enough for him to be unable to work as a joiner and farmer. Things must have been very desperate before they resorted to poor relief. He ‘recovered’ in a few weeks, it seems. Unresolved grief from the deaths of three brothers and his father in just over two years in the late 1860s may well have been at the root of it.

School days

Pa enjoyed school and did well, despite a particularly savage teacher. On one occasion, he had to do sums for homework but there was no money for a notebook, so, with some enterprise, he used the blank margins of the local paper, The Orcadian. Ink pens and soft newpaper do not mix well; the ink ran and he lived in fear of reprimand but on this occasion it did not come. To sustain them through the day, he and his siblings set off to school with a piece of oat bannock each; this was sometimes eaten before they reached the school, less than a mile away.

Economics prevailed, however, and Pa effectively left school at the age of 12 when he was taken out in the summer months to herd cattle. Going back later in the year, he and others like him had fallen behind and the teacher did not bother with them. “Stick in at the school”, he would say to me. How proud he would have been that all six of his grand-daughters went on to higher education, as did his older daughter and his youngest sister, Mimie. (Boys can be farmers; that is different.)

Emigration

After working on farms in Orkney, including Swanbister, the Hall of Clestrain, and Lingoe, Orphir – the last with his brother John – he emigrated to New Zealand in December 1913. This was not at all uncommon for young Orkney men at the time. More unusually though, he was engaged to my grandmother, Jessie Sclater, when he left. Three older brothers, Alec, Tommy and Bob, had already emigrated: Alec to Australia; the other two to Canada where Bob died in December 1910.

The “new world” was undoubtedly a place of great opportunity but the poverty and lack of work in Orkney was a great driver too. Pa sailed from London on 4 December 1913 on the SS Ionic with his lifelong friend, Jim Tait from Clestrain, Orphir. In New Zealand, he worked mainly on sheep farms in South Island in the Methven and Canterbury areas.

War

James Slater, NZ Mounted Rifles

World War One eventually intervened and he enlisted with the New Zealand Mounted Rifles on 18 October 1917. His active service began in March 1918 and on 10 October 1918 he sailed for the Middle East and Suez. He was promoted to the rank of corporal and travelled all through, what was then, Mesopotamia, what we would now know as parts of Iraq, Kuwait, Saudia Arabia, Syria and Turkey. He found himself in Jerusalem and in the Temple, where, against all orders, he took a memento, a small coin-shaped metal object, which my mother remembers from her childhood. He also brought back malaria, which dogged him, on and off, throughout his life. In July 1919, with the war over, he embarked once again for New Zealand.

New Zealand returners

Jim Tait, Tom Rendall and Geordie Hume, three of my grandfather’s friends, were also New Zealand returners.

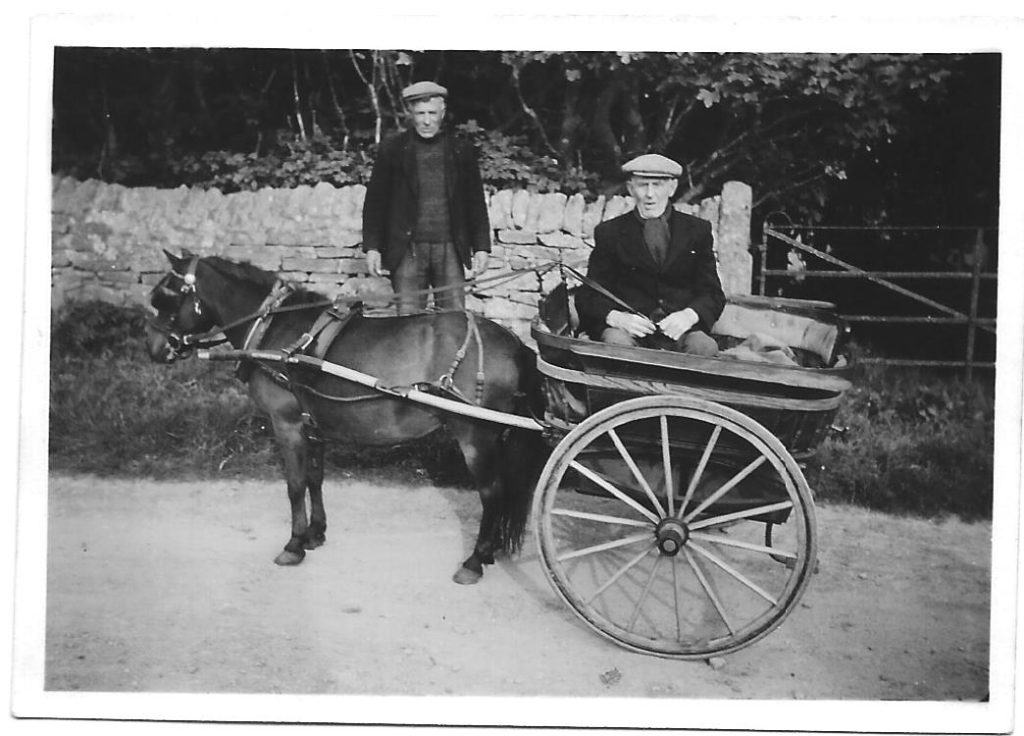

James Slater, Geordie Hume (in gig), at Yarpha

Geordie credited himself with saving Pa’s life when he was terribly sick in the Bay of Biscay on the return voyage. My grandfather was very concerned that his friend also save two stuffed birds he had taken with him, a kea and a kiwi, which sat in my mother’s home as she grew up but, alas, disappeared (dumped?) at some point after my grandfather’s death.

Marriage and family

Pa and grandma eventually married on 16 November 1921 at Groundwater, Orphir, Jessie’s home. The next morning, Pa rose early and cycled seven or eight miles to the sale of implements and stock at Hogarth, Rendall (map). He had just bought this small farm with money saved up in New Zealand. With the break-up of big estates underway, the early 1920s in Orkney were a good time for people looking to buy their own farm..

Hogarth was home to James and Jessie for the next 21 years. Four of their five children were born there between 1922 and 1927: James William, Victor, Tomima Jessie (my mother, always known as Tess) and Barbara. The youngest, Ian, was born at Kebro, Orphir, Jessie’s home, in 1928. Over the years, he added to the farm, buying Nearhouse and renting other crofts. I say ‘he’ deliberately for my grandmother was rarely consulted though her skill as a manager of money and her sheer hardwork, both inside and out, played quite a part in the success of the farm.

Back: James Slater, Jessie Slater, Jeanie Harcus (Sandyha’), Jock Taylor (The Lyde) Front: Barbara Slater, Tess Slater (head of Lily Sclater, sister of Jessie, at the back) Around 1929

Innovation

The years in New Zealand continued to influence Pa for he had seen different ways of working there and was keen to try new things. Jim Nicolson in his book Rendall in the 1930s described him as “hard-working” and “an enterprising farmer” (p73). Working with the Department of Agriculture, Pa tried a crop of linseed one year but did not repeat the experiment as it was not very successful. He also bought the first Lister diesel engine in Orkney to run the farm mill. As a result, he was one of a group of farmers invited to visit the Lister works in Coventry at some point in the 1930s. My mother recalls that he was away for about a week, travelling with the clothes he stood up in (there was only one set of best clothes) and his cut throat razor. His sister, Annie, who lived in Kirkwall and had married rather well, provided him with a Gladstone bag so that he looked more respectable!

Rules

During WW2, the government encouraged farmers to plough out more land and he had a job inspecting farms to ensure their crops reached the required standard. He did not pass them all; he was resolute about quality, which did not make him popular with everyone. Jim Nicolson, in the book referred to above, describes the sheep-dipping facilities Pa set up at Mossater, one of the crofts he rented:

“On dipping day neighbours bring their few sheep for dipping in accordance with Department of Agriculture regulations, and James… stands with his Elgin pocket watch ensuring that each sheep is dipped for the compulsory one minute.”

Back to Orphir

In 1942, at the age of 52, James sold up in Rendall and took on the rental of Yarpha, home farm of the Smoogro estate in Orphir. (Map.) In some ways this was a surprising move, going from being an owner to tenant, but Yarpha was a substantially bigger farm. He and his sons had looked at a number of other farms, assessing them on the centrality of the steading to the lands, among other factors. Yarpha certainly ticked that box but it is almost certain that the tenancy was a step rather than the ultimate goal.

His probable game plan paid off for J Storer Clouston, author, historian and owner of the Smoogro estate, died in 1944. Death duties could be a considerable burden and in the ensuing sale, James (Pa) bought Yarpha and two other units in 1955. Later that year, he also bought Dale from Storer’s son. Along with Swenabow (pronounced Sweenabu), which he bought in 1946, his farm was now over 170 acres. With the addition of other crofts, including Langbanks and Highbreck, his estate by the time he died was over 200 acres.

The sasines provide an insight into how he bought these farms. It was not banks but individuals who lent him the money, mainly Kirkwall solicitors, Thomas P Low, for Nearhouse, Rendall, and Cecil ES Walls, for Yarpha and Dale. The £1700 he borrowed from the latter in 1955 was paid back in 1962.

The house

Like many farmers, land was far more important than the farmhouse to him. But on that subject he met his match in the redoubtable “aunties o Kebro”, his sisters-in-law, not least Auntie Violet. With a good farm like Yarpha, it was high time they had a proper bathroom. So, with reluctance and a grant, he agreed to modernisation and the installation of proper facilities in 1962!

Last years

From 1962, I have a fairly clear memory of Pa and I very much liked going to Yarpha. Treats included a ride from the stable to the watering trough on the back of Nellie, the white half Percheron horse. There were still four heavy horse on the farm, for Pa, innovator though he was, liked horses very much. Mechanisation was increasing but horse were far more suited to some jobs, like carting turnips out of a wet field. For him, they had their place alongside the David Brown tractors, as he said in a recording for radio made by Ernest Marwick in 1964. There were three by that time. You can listen to the recording here (actual interview starts about 4 minutes in, mainly horse sounds before that).

(Orkney Archive Reference D31/TR/12/2. Used with permission.)

By his death, I think there were two horses and two tractors.

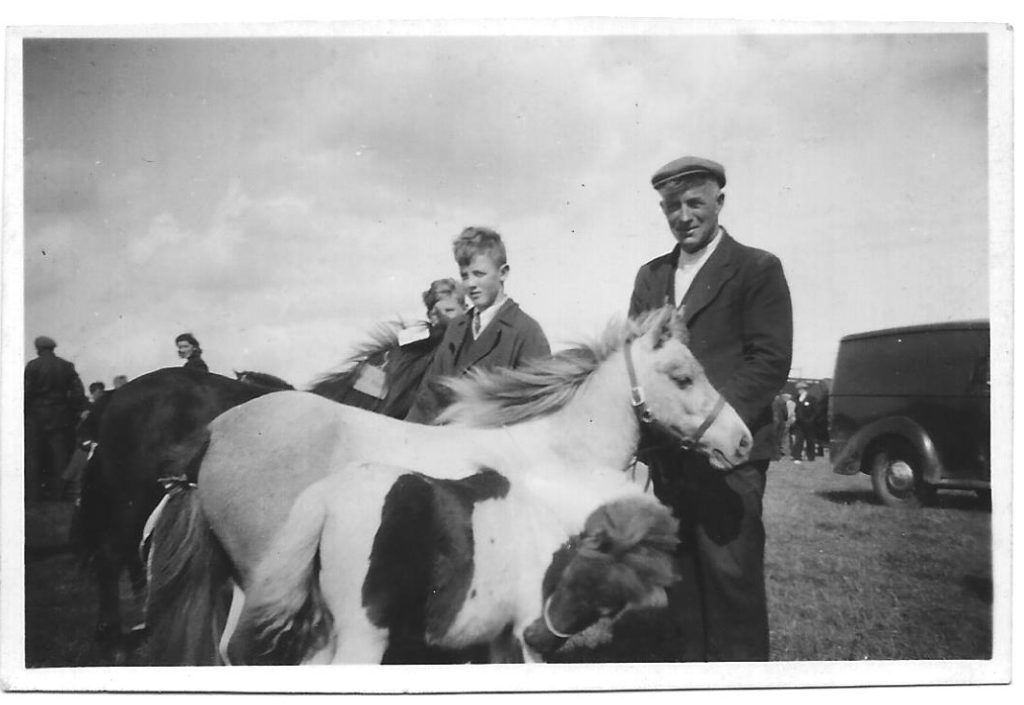

Pa at a show. He bred Shetland ponies too.

And he was a practical man: his Christmas present to me, aged three and bit, was a red toy wheel barrow! I cherished it.

Pa died on 25 January 1967 from pancreatic cancer. He had done well in life, through resolution, determined hard work, and an element of flair. Unpredictable, quirky, tough; “dour, duggid and determined” as my father said. Yes he was all of those too.

The final post for the 2018 #52ancestors challenge, on the theme ‘Resolution’.

I have really enjoyed your 52 ancestors posts. What fascinating ancestors you have!

Best wishes for a very happy and healthy 2019. Hope to see you at the SAFHS conference in Wick in April.

Thanks. I've quite enjoyed writing the posts. Happy New Year to you too. And yes I hope to be at the SAFHS Conference.

My grandfather's cousin's fiancee went to New Zealand on the Ionic in 1907 and I have her diary which I have transcribed. Would you like to read it?

Hi, yes that would be interesting. Thanks for the offer.